The unit delivered, whilst not entirely an open inquiry was designed to give students a large amount of autonomy and self direction in their choice of topic and the direction it would take, however the teacher would still provide guidance and scaffolding for the methodology of their inquiry. This coupled inquiry approach allows the students to build and develop the skills required for true open inquiry. Students were asked to identify a group or person in history and examine their acquisition and use of power and the role it has played in historical change. The theme – Studies of Power, is part of the Queensland Modern History Curriculum from the Queensland Curriculum and Assessment Authority (QCAA) and the task was designed to meet all three of the syllabus criteria; Planning and using an historical research process; Forming historical knowledge through critical inquiry and; Communicating historical knowledge. Furthermore, whilst the new Australian Modern History Curriculum has not yet been implemented in Queensland the task clearly also provided the opportunity to meet the overarching aims of the new curriculum;

- understand key developments that have helped define the modern world, their causes, the different experiences of individuals and groups, and their short and long term consequences

- understand the ideas that both inspired and emerged from these key developments and their significance for the contemporary world

- apply key concepts as part of a historical inquiry, including evidence, continuity and change, cause and effect, significance, empathy, perspectives and contestability

- use historical skills to investigate particular developments of the modern era and the nature of sources; determine the reliability and usefulness of sources and evidence; explore different interpretations and representations; and use a range of evidence to support and communicate an historical argument. (ACARA 2012)

Students were also provided opportunities to add depth to their learning by engaging in several of the General Capabilities identified by ACARA as playing an integral role in equipping students to live and work successfully in the twenty-first century. Table 1 below illustrates the General Capabilities addressed in the task and the ways in which students could engage in them.

Table 1: General Capabilities Demonstrated in Inquiry Unit. Adapted from ACARA (2012)

The task was also grounded in the pedagogy of Anderson and Krathwohl’s (2001) revised Bloom’s taxonomy. Figure 1 below illustrates how students begin their inquiry with basic background research before moving through evaluating and analysing the impact and significance of the power of their individual or groups to the modern world. The task culminated in students creating this into a historical argument to share with the class in a format of their own choosing.

Figure 1: Bloom’s Revised Taxonomy as Applied to the Inquiry Unit

As I had “inherited” the class and the Inquiry Learning Activity I was delighted to find that the construction of the task outlined above, provided ample opportunity for the students to function in the Transformative Window, from the GeSTE framework suggested by Lupton & Bruce (2010). Students were simply given a thematic focus of the role power has played in historical change, and had the freedom to choose their own topics and develop their own questions to analyse the acquisition and use of power by their group or person and the consequences for history. As students could develop their own hypothesis in response to their research and present their evidence and argument in any multi modal genre there was plenty of opportunity for students to use their research and information for personal empowerment, and to challenge and question the status quo.

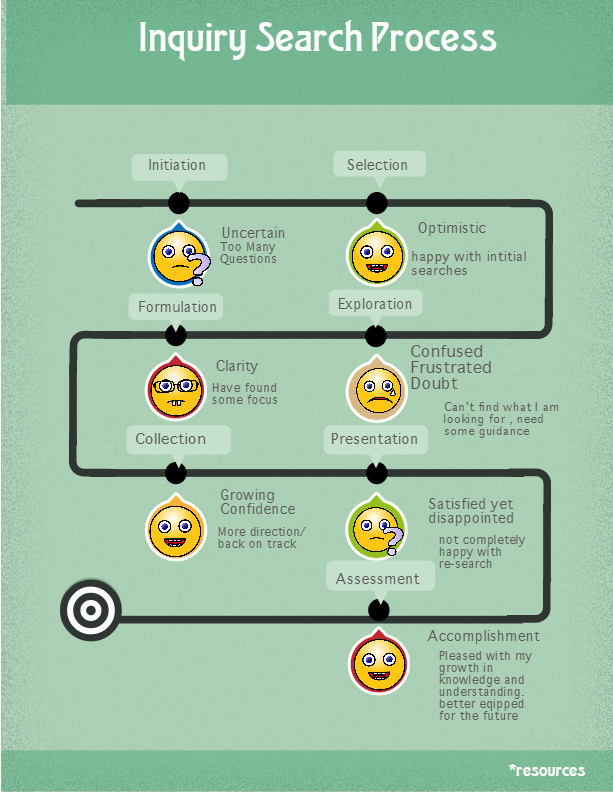

It is this critical literacy that is an essential element of the Transformative Window, as it takes students learning above the social and contextual frame of information literacy characteristic of the Situated window, or the surface and more limited view of information of the Generic Window of Lupton’s GeSTE Framework (2010). However, since guided inquiry requires “careful planning, close supervisions, ongoing assessment and targeted intervention to gradually lead the students to independent learning”(Kuhlthau, 2010). I knew I would need to be heavily involved in scaffolding the process and implementing a range of tools and frameworks to assist the students achieve this higher level. However, despite the design of the unit there were a number of barriers that prevented many students from achieving the transformative window, with only some achieving the situated window and many remaining stuck in the surface view of information characteristic of the Generic Window. I believe a key reason for this issue was the lack of an overall guiding information literacy and inquiry model to promote an Action Research cycle such as Kuhlthau’s Guided Inquiry Design or Brunner’s The Inquiry Process. Further to this The SLIM toolkit findings indicated that despite the use of a range of scaffolds, students were struggling with researching, particularly in finding, assessing and using primary and scholarly sources to develop their understanding as well developing focus questions that would frame their inquiry in the context of the essential questions of power. As a result, outlined below are some changes that I would recommend be made to this and future units regarding the use of a guided inquiry design that promotes a greater emphasis on an action research cycle as well as changes to the inquiry questioning frameworks used that may help push students to a more transformative understanding.

The unit was designed to reflect the QCAA’s Aspect of Inquiry model that is the underlying principal guiding the senior study of Modern History in Queensland (Figure 2)

Under this model any inquiry a student undertakes must include these five aspects. In order to investigate these aspects a Structure for Student Inquiry is provided (see Figure 2), that links the aspects of inquiry to a process that is designed to meet the three objectives outlined by the QCAA of an inquiry task of; Planning and using an historical research process; Forming historical knowledge through critical inquiry and; communicating historical knowledge.

Whilst the Structure For Student Inquiry model includes opportunities for students to reflect on historical argument and make personal connections and responses, the structure of the design to centre around meeting the three Objectives and Criteria of the Queensland Modern History Syllabus, does not encourage the students to view their inquiry as part of a research cycle or assess and evaluate the process. The Process of Inquiry elements under each objective act more as a checklist of skills characteristic of the Generic Window and do not replicate the authentic processes of inquiry in which students engage in the outside world (Lupton, 2012). As a result the students’ approach to their research was very linear and struggled to move to the Situated or Transformative windows.

This linear approach was also encouraged by the use of an Investigation Strategy Scaffold (Figure 3) which was designed to translate the Structure For Student Inquiry model above into a systematic approach for the students to use to guide their inquiry. Whilst the Investigation Strategy guided students to reflect throughout their inquiry it did not encourage students to revisit their questions and conclusions or pose new questions and ideas.

Figure 1 Investigation Strategy. Used with School Permission

The findings from the SLIM Toolkit questionnaires revealed that many students rushed through the initial stages and moved straight to formulating their focus questions without having properly explored their topic. By implementing Kuhlthau’s Guided Inquiry Design Process which makes explicit the physical and intellectual steps that that students need to complete an inquiry, students would have the opportunity to learn strategies in locating, evaluating and using a wide range of media and a variety of texts and put these strategies and skills into action throughout the inquiry process. Furthermore as students move through the stages of an Information Search Process they learn “the process of inquiry as well as how they personally interact within that process” Kuhlthau (2010). Figure 2 below illustrates how Guided Inquiry Design could be used as a framework for the students to follow for their inquiry into power.

Figure 2: Suggested Guided Inquiry Framework adapted from Kuhlthau’s Guided Inquiry Design to direct students in their inquiry.

The absence of a Guided Inquiry Design model, meant that the students missed the key early phases of their inquiry. Whilst the task was designed to enable students to ask essential questions, the regular teacher handed it out before the holidays prior to my taking the class. As a result most students skipped the Open and Immerse phases of inquiry and and moved straight to doing background research and creating generic focus questions for which they could find “an answer”. This first step is a key part of Kuhlthau’s Guided Inquiry design where students experience an open invitation to inquiry at the beginning of the inquiry process. Kuhlthau (2012), asserts that this is a vital phase in the process as it sets the tone and direction of the inquiry. The aim at the beginning of the task is to stimulate the students to think about the overall content of the inquiry and to connect with what they already know from their experience and personal knowledge. I would recommend that the next time the unit should begin with a greater emphasis on the Open phase of the Guided Inquiry Design and focus on discussing essential questions. The rush to get on with the task meant that the students missed an invaluable opportunity to engage with the bigger essential questions of the inquiry and made it difficult for some to move beyond delivering a historical narrative. Murdoch (2012) argues that interrogating the essential questions that drive an inquiry is a critical component of the planning process, and that in doing so, teachers inquire themselves – identifying the underlying threads and ideas that make the journey important. Wiggins (2007) also argues that these big-idea or essential questions lead to relevant and genuine inquiry, provoke deep thought and new understandings as well as stimulating a rethinking of ideas and assumptions. As a result, these questions signal to students that education is not just about learning “the answer”, but about learning how to learn. As the students had previously completed a unit on Hitler, starting with a discussion of power and the essential questions that were raised regarding this study may have helped reframe their inquiry so that the focus was more conceptual and investigative.

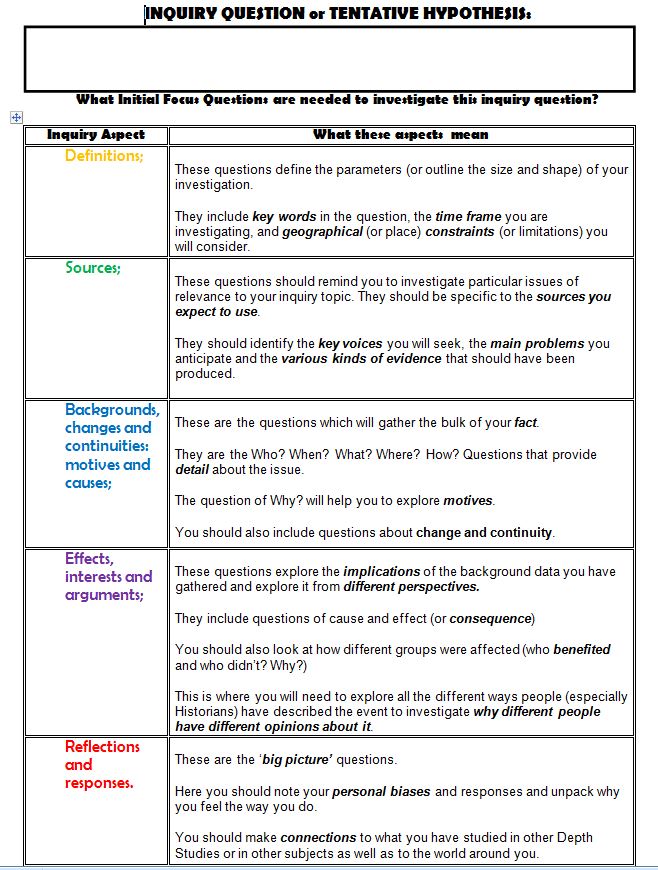

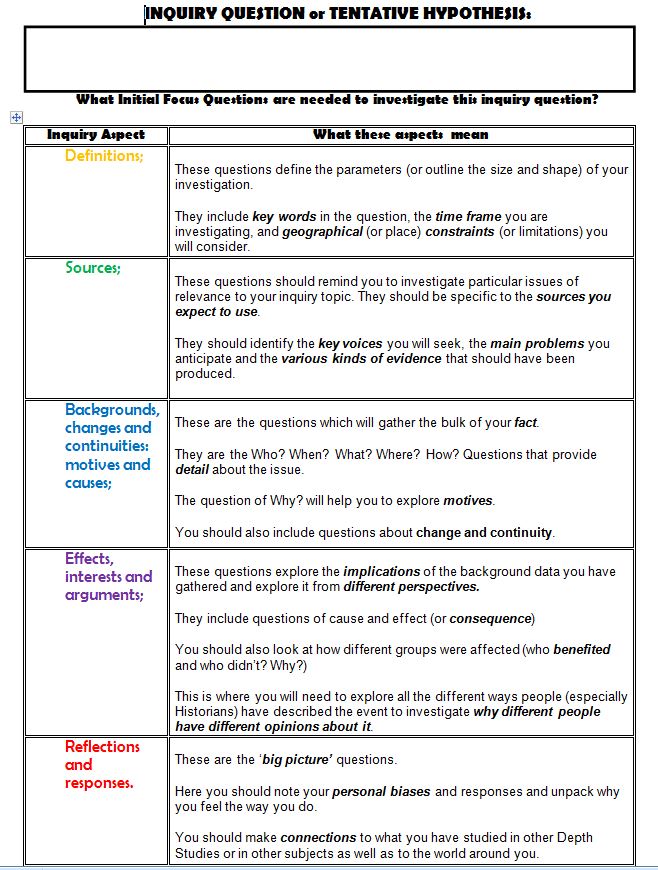

The students were given a copy of the Aspects of Inquiry framework (See Figure 2 Below) adapted from the Queensland Modern History Syllabus which is used to assist them to pose their own focus inquiry questions. This framework was designed to move the students through the immersion phase of their inquiry into the exploratory stage as well as provide guidance for addressing each of the 5 key aspects of their inquiry under the QCAA model. The tool includes some excellent prompts for students, and provides a locus for the aspects of their inquiry and their associated focus questions.

Figure 2 Aspect of Inquiry. Used with School’s Permission

Questions or prompts such as

note your personal biases and responses and unpack why you feel the way you do

and

make connections to what you have studied in other Depth Studies or in other subjects as well as to the world around you.

encourage students to respond to their inquiry in a deeply personal way as well as critically question and challenge the information to push them to the transformative window.

However despite the potential this tool offers initially the students were not confident in its use, and needed assistance and greater modelling to construct their own questions. Whilst this framework provides provides prompts for students to interrogate the inquiry process and to ask data and information seeking questions that are what Lupton (2012b) argues are productive and evaluative, students also needed the assistance of a generative scaffold to provide the means to ask essential questions. Furthermore, whilst the sample focus questions suggested in the tool do not specify the order in which these aspects may be undertaken in the inquiry, the linear design of the scaffold meant that the students saw it as a checklist of questions to work through. This does not reflect the circular nature of inquiry or action research, where inquirers may return and revisit their questions or develop new questions as they progress through their inquiry. For example throughout the course of an inquiry, issues of definition, or reflections and responses may reappear several times. In future iterations of this task it is clear that at this point greater intervention from the teacher is required. I would like to redesign the Aspects of Inquiry tool so that a more explicit questioning framework be included under each aspect of the inquiry and attempt to align the different Inquiry Aspects against the phases of Kuhlthau’s Guided Inquiry Design. However the use of an explicit questioning framework must also be tempered with a need to teach students how to formulate their own questions. Utilising a generative scaffold such as the Question Formulation Technique (Rothstein & Santana 2011),could help students to learn how to produce their own questions, improve them, and strategise on how best to use them.

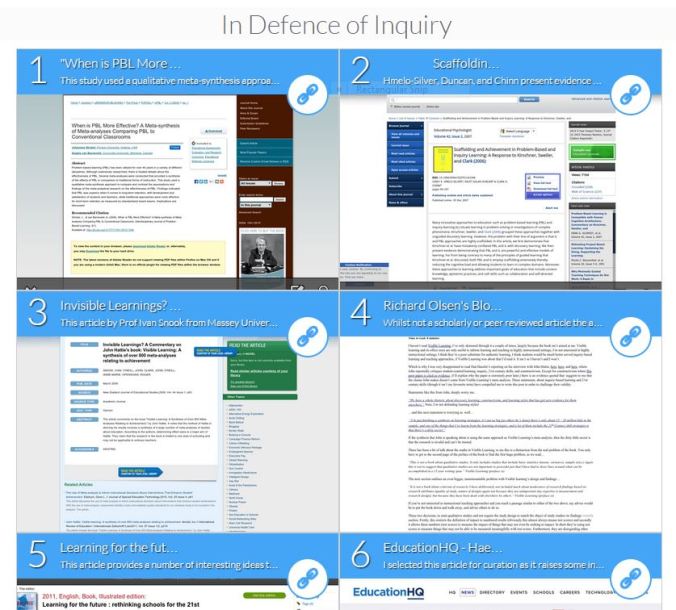

In order to move beyond the Generic Window, students needed to be able to question and interrogate their information on a more epistemological level. Students were encouraged to use an Annotated Literature Review using a CUP technique (Figure 3) as an evaluation framework to assist them to analyse their sources and research.

Figure 3 CUP TOOL. Used with school permission

Whilst the students have previously used this tool many times, in our feedback sessions it was apparent that most students focused on the Credibility and Utility of the source with little attention paid to perspectives. Further to this, whilst there are some questions under the Perspective heading that point towards Situated and Transformative windows such as

How would the time of production affect selection or evaluation of information?

What gaps and silences in information are evident?

the students had not properly engaged with these and were functioning predominantly at the surface level of evaluating information. The inclusion of questions that aim to reveal the epistemology of the information would increase the students’ ability to move to the situated and transformative windows. I would suggest incorporating use of the SCIM-C strategy as an evaluation framework to help students not only interpret historical primary sources and reconcile various historical accounts, but go further and use them to investigate meaningful historical questions. When students use SCIM-C to examine a source they move through the first four phases of Summarising, Contextualising, Inferring, Monitoring. Then after using these phases to examine a number of sources they compare these sources collectively in the fifth phase. Each phase includes a spiral of 4 questions that encourages a rigorous level of engagement with each source. In particular questions in the monitoring and inferring stages such as:

What inferences may be drawn from absences or omissions in the source?

would better assist students to question sources beyond the surface level and encourage them to take the time to “linger and learn from the source in order to develop and write an historical interpretation” (Doolitlle, Hicks and Ewing, 2004)

A significant barrier to the students achieving the transformative window was the construction of the marking criteria and standards. The task directly adopted the Criteria and Standards from the Queensland Curriculum and Assessment Authority (QCAA) for multi modal research tasks in the Modern History Syllabus from 2004. The standards and criteria appear to assess the students’ learning on a surface level which creates a real tension between the aims of the inquiry activity and the assessment of the students’ work. Close inspection of the criteria reveals little opportunity to demonstrate achievement in the transformative window as the marking criteria mainly presents a checklist of information literacy skills from the generic window. For example – A level descriptors included:

Creates and maintains detailed, systematic, coherent records of research that demonstrate the interrelationships of the aspects of inquiry

Demonstrates initiative by locating and organising primary sources that offer a range of perspectives on chosen topic and issues of power.

Evaluates the relevance, likely accuracy and likely reliability of sources.

As a result it was difficult to move the students from the generic window, and they became increasingly confused as to the direction they should be taking with their assessment piece. It became quite clear that the feedback and intervention I was giving them to develop learning and understanding in the situated or transformative window, was not reflected in the marking criteria for their piece.

As students demonstrate their knowledge of content and skills through the process of inquiry, the assessment of Inquiry Learning should be both formative and summative. Whilst given the small numbers of students, I was able to provide a great deal of feedback throughout the unit as formative assessment, the construction of the marking criteria for the summative assessment did not match the aims and design of the Inquiry Learning Activity. Instead the assessment task was focused on the achievement of skills and processes as well as content and context. It was this tension that caused the students the greatest confusion. According to Kuhlthau, Maniotes & Caspari, (2007) the major challenge of inquiry is to design an instrument to provide assessment information to the teacher as well as promote self – awareness among students. If Inquiry learning requires that students demonstrate their understanding through explanation, interpretation and application (Harada, 2004), then the final presentation should only make up part of the assessment and have equal footing with the process the student has followed. Kuhlthau (2007) argues that the ideal instrument could be used as an intervention for reflection while serving as an assessment of learning progress. In an ideal world I would revise the marking criteria to establish a greater emphasis on their research logs where I am better able to assess their construction of knowledge and reflections on the process. To help students achieve the transformative window, the marking criteria should have an emphasis on outcomes for the individual and society, and acknowledge learning that reflects a capacity to be informed citizens with the skills, including analytical and critical thinking, to participate in contemporary debates. This is supported by Wyatt-Smith, Klenowski, and Colbert (2014), who argue that we should engage in assessment practices that have as their focus improved outcomes for students. These outcomes may be personal, academic or social, depending what is valued by the communities in which the students live. The use of the SLIM toolkit should also be continued as formative assessment and feedback for the teacher as it provides an easy-to-use and reliable measurement of the growth of student learning through Guided Inquiry. In addition the SLIM toolkit provides evidence of student learning in multidimensional ways including growth of knowledge of their curriculum topic, interest, feelings, and experiences during the inquiry process, and their reflections on their learning.

Unfortunately however, we cannot ignore the context in which we work and that as a senior subject the unit needs to be assessed in line with the current Queensland Syllabus so that the students’ work will meet the requirements of the QCAA. In addition, the desire to set demanding standards of achievement for students and to know whether these are being achieved has led to a considerable increase in attention to assessment as well as current moves towards standardised assessment tools in Queensland. This means that we are more likely to see the scenario in Figure 4 below, than we are to see real changes to the design of assessment criteria in the subject

Figure 4: Current Assessment, created by author. Based on an original idea by whatedsaid

By implementing the above recommendations to the Inquiry Unit the learning experiences of future students of Senior Modern History at the school would be enhanced. The frustration of some students discussed previously in my Findings post of how different the expectation and aims were for this unit means it is essential to acknowledge that similar adjustments must be made to the units and tasks across all years of history study (and indeed all curriculum areas) in order to provide a consistent continua of skill development.

REFERENCES

Anderson, L.W. (Ed.), Krathwohl, D.R. (Ed.), Airasian, P.W., Cruikshank, K.A., Mayer, R.E., Pintrich, P.R., Raths, J., & Wittrock, M.C. (2001). A taxonomy for learning, teaching, and assessing: A revision of Bloom’s Taxonomy of Educational Objectives (Complete edition). New York: Longman.

Doolittle, P., Hicks, D., & Ewing, T. (2004). SCIM-C Explanation: a strategy for interpreting history. Retrieved October 20, 2015, from Historical Inquiry: http://www.historicalinquiry.com/scim/index.cfm

Harada, Violet. H. and Joan M. Yoshina. (2004). Inquiry Learning through Librarian Teacher Partnerships. Worthington, Ohio: Linworth Publishing, Inc.

Kuhlthau, C. C. Maniotes, L. K., & Caspari. A. K. (2007). Guided inquiry: Learning in the 21st century. Santa Barbara, CA: Libraries Unlimited.

Kuhlthau, C. (2010). Guided inquiry: School libraries in the 21st century. School Libraries Worldwide, 16(1), 1-12.

Kuhlthau, C., Maniotes, L., & Caspari, A. (2012). Guided Inquiry Design: A Framework for Inquiry in your School, Santa Barbara, CA: Libraries Unlimited.

Lupton, M & Bruce, C (2010) Windows on information literacy worlds : generic, situated and transformative perspectives. In Practising Information Literacy : Bringing Theories of Learning, Practice and Information Literacy Together. Centre for Information Studies, Charles Sturt University, Wagga Wagga, N.S.W., pp. 4-27.

Lupton, M. (2012a). What is Inquiry Learning. [Web log]. Retrieved 23 October 2015 from https://inquirylearningblog.wordpress.com/2012/08/22/what-is-inquiry-learning/.

Lupton, M. (2012b). Collecting Questions. [Web log post]. Retrieved 20 August 2015 from http://inquirylearningblog.wordpress.com/.

Murdoch, K (2012). Walking the world with questions in our head [Web log]. Retrieved 20 October 2015 from http://justwonderingblog.com/2012/10/28/walking-the-world-with-questions-in-our-heads/

Rothstein, D. & Santana, L. (2011) Teaching students to ask their own questions.Harvard Education Letter. 27:5 http://www.hepg.org/hel/article/507#home

Wiggins, G. (2007) What is an essential question? Big ideas. Authentic Education. http://www.authenticeducation.org/ae_bigideas/article.lasso?artid=53

Wyatt-Smith, Claire; Klenowski, Valentina; Colbert, Peta (2014). Designing Assessment for Quality Learning.

![Upon reflection by Vivian Chen [陳培雯], on Flickr Upon reflection by Vivian Chen [陳培雯], on Flickr](https://farm5.static.flickr.com/4128/5224378646_2ceb4e99ec.jpg)